Food Science: Single Celled Fungi & Fungal Protists

HORECA Interview: Arthur Grima, Marketing Director, MTA

January 14, 2024

Mercury in St Julians: Where Hospitality and Culinary Excellence Converge

January 25, 2024In the last couple of issues we dove into the wonders of both macro and micro fungi and their fascinating diversity in the kitchen. From the finesse of truffles to the floral funk of miso, these fungi have shaped, and are still shaping international cuisine as a whole.

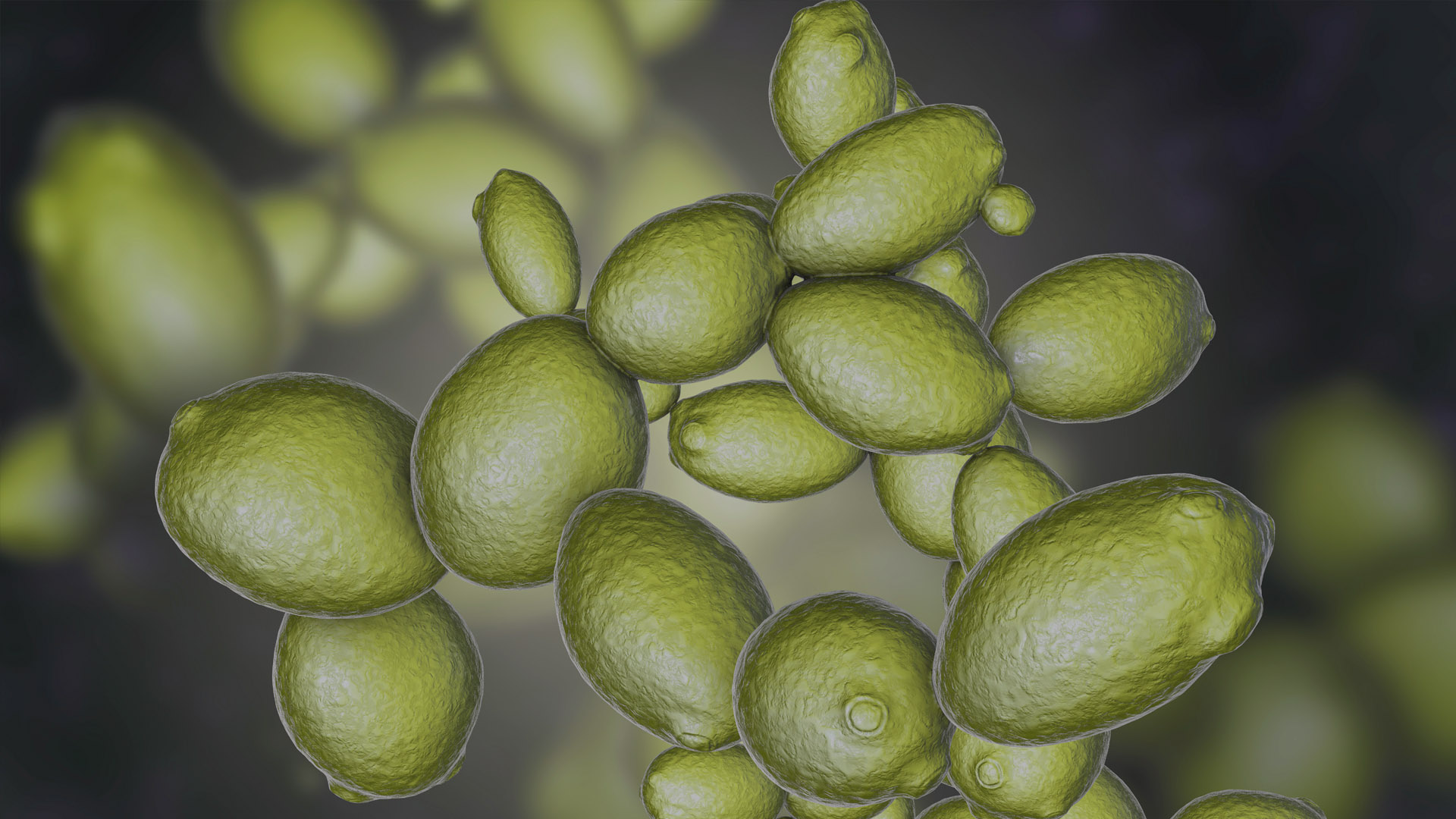

However, there are families of fungi whom we have a symbiotic relationship with, who have given us nutrition for centuries, who have shaped civilisation as a whole, and these are single celled fungi; yeasts in particular.

There are several hundred varieties of yeasts found across the globe and they’re almost everywhere, on our skin, in our stomachs, on the rinds of fruit and vegetables, and… in and on our everyday foods. Not only that, but we eat yeasts and their by-products on a daily basis, probably several times a day, purposefully. Bread, chocolate, coffee, cheeses, hams, pickles, preserves, wine, beer, alcohols… in general, really, and so many other daily staples that wouldn’t exist without them.

It doesn’t stop there, they create new flavour compounds and nutrients, making food and beverages that much more exciting, not to mention the varieties that can preserve food. Some varieties like Khams Yeast makes food taste fungal and disgusting, like that white layer you get floating on top of your olive brine. Others like tinea and candida (of which there are members we eat) can cause infections, but thankfully we will only cover the wonders of edible varieties.

Yeast is so important that we now use isolated, lab grown strains, meant to give a specific flavour or carry out a specific function. Like Saccharomyces Cerevisiae which has now been commercialised globally in various forms, most commonly as bread yeast, brewer’s yeast or chardonnay yeast as examples.

This variety mainly consumes carbohydrates, it feeds and replicates, and as a by-product it leaves behind alcohol and carbon dioxide. The more sugar there is the higher the alcohol volume (not too high mind you as too much sugar would affect the water activity ratio), and as the yeast feeds it begins to unlock new compounds previously bound in these large carbohydrate chains.

In wine yeast converts the roughly 17% of carbohydrates found in the grapes into an alcoholic beverage far more complex than boring old grape juice. In fact, during the fermentation process, the grape juice goes from having a measly 200 flavour compounds to a jaw dropping 600 flavour compounds as well as creating the sparkle in champagne.

In bread it consumes the carbs, creating new nutrients and flavour compounds, mostly alcohol-based compounds. The yeast also creates carbon dioxide, that gets trapped in the gluten structure where most of the flavour gets trapped in the form of gas. These little friendly fungi, especially wild varieties found in sourdough bread also predigest some of the grain for us, making them easier on our stomachs to eat, this includes small amounts of gluten.

Cacao is a bland and bitter “bean” surrounded by a grapefruit-like tasting pith, both carrying very little flavour compounds, but once yeasts come into the equation magic happens. Now the main reason why raw cocoa beans have so little flavour is that the proteins are so tightly bound that everything is trapped in its complex, dense matrix. Right after harvest the resulting mass of beans and pith are left to ferment in the jungle, wild yeasts jump right in consuming the sugars in the pith, creating fantastic new flavour compounds and alcohol, once alcohol is created wild acetobacter varieties join the party and consume the alcohol turning it into acetic acid also known as vinegar

The acid breaks small holes in the bean allowing the yeasts plus other bacteria and fungi to enter the bean and break down this once dense, flavourless object (roughly 150 compounds) to one of the most complex foods in existence. In fact once the fermentation process is complete, the resulting beans contain over 700 new compounds, some of which lead to flavours resembling wine, coffee, vanilla, and other various fruits and spices.

This also means that the oldest preservative in the world, vinegar, wouldn’t exist without this single celled fungi, acetobacter and other acetic acid producing bacteria, like the ones found in kombucha need to feed off small amounts of alcohol, and alcohol is almost always created by yeast. We aren’t talking about alcohol flavour compounds, those are also found naturally in most foods, although yeasts do produce them also.

In the same light, wild yeasts are also responsible for debittering olives and capers, two ingredients which in their raw form are bitter and unappetising. Once placed in a super salty brine magic happens, the salt helps to remove some of the bitterness, and mask some more. But due to the high percentage of salt only a few species of bacteria and fungi can live in the brine, yeasts being a few of them, they start to break up the dense proteins in the ingredients, letting the brine permeate the structure and release even more bitterness into the brine making them edible. In beer brewing different saccharomyces species are used to convert the carbs in the boiled grain broth (known as sweet wort) into alcohol and turning the boring sweet liquid into a delicious, lightly alcoholic beverage.

It’s not only S. Cerevisiae that’s used in beer making, some brewers prefer fermenting at colder temperatures to S. C’s twenty plus Celsius preferred growing range, so these brewers would opt for cold loving varieties like S. Uvarum or S. Carlsbergensis. These varieties also lead to different flavour compounds and one variety like Torulaspora is specifically grown to produce German wheat beers and release very unique flavour compounds not seen in other beer styles.

Yeasts are versatile and can live almost anywhere, so rest assured that if it’s fermented yeast, it’s there working hard to transform a product. Even things like soy sauce, fish sauce and miso rely on yeasts for the majority of their fermentation.

Similarly there are also fungal protists. Protists are single celled organisms that don’t fall under a specific family and don’t really act like plants, animals or fungi, but sometimes they do, these can be fungal like the 800 strong varieties of slime moulds, but they can also be algae or amoebas. But mostly we will be focusing on slime moulds, the smartest single celled organisms, responsible for ruining most of our foods as well as helping scientists and architects design roads and public transport routes in the most efficient way possible, helping us get our foods faster.

We can prevent these protists from destroying our food by low temperature heating, usually at around 48C for a few seconds is enough to kill them off. But one particular variety fuligo septica or in English, “dog vomit slime mould” (I know, terrible name) is actually edible and delicious and is commonly found all over to world, and has the flavour and texture of scrambled eggs. Although I doubt it will be a hit in restaurants any time soon.

Needless to say, if you eat it on a daily basis, if it’s delicious and nutritious, rest assured single celled fungi were probably involved in making it. So lets thank these little creatures for without them our daily staples in the world of food and beverage wouldn’t be possible.

Keith Abela

Keith Abela is a forager, product developer and local food consultant. Who spends all of his time researching the delicious, rare and unique ingredients Maltese nature has to offer. He has a particular interest in multisensory flavour perception and all things fungus.

Click here to see Horeca Issue 14 online

It doesn’t stop there, they create new flavour compounds and nutrients, making food and beverages that much more exciting, not to mention the varieties that can preserve food. Some varieties like Khams Yeast makes food taste fungal and disgusting, like that white layer you get floating on top of your olive brine. Others like tinea and candida (of which there are members we eat) can cause infections, but thankfully we will only cover the wonders of edible varieties.

Yeast is so important that we now use isolated, lab grown strains, meant to give a specific flavour or carry out a specific function. Like Saccharomyces Cerevisiae which has now been commercialised globally in various forms, most commonly as bread yeast, brewer’s yeast or chardonnay yeast as examples.

This variety mainly consumes carbohydrates, it feeds and replicates, and as a by-product it leaves behind alcohol and carbon dioxide. The more sugar there is the higher the alcohol volume (not too high mind you as too much sugar would affect the water activity ratio), and as the yeast feeds it begins to unlock new compounds previously bound in these large carbohydrate chains.

In wine yeast converts the roughly 17% of carbohydrates found in the grapes into an alcoholic beverage far more complex than boring old grape juice. In fact, during the fermentation process, the grape juice goes from having a measly 200 flavour compounds to a jaw dropping 600 flavour compounds as well as creating the sparkle in champagne.

In bread it consumes the carbs, creating new nutrients and flavour compounds, mostly alcohol-based compounds. The yeast also creates carbon dioxide, that gets trapped in the gluten structure where most of the flavour gets trapped in the form of gas. These little friendly fungi, especially wild varieties found in sourdough bread also predigest some of the grain for us, making them easier on our stomachs to eat, this includes small amounts of gluten.

Cacao is a bland and bitter “bean” surrounded by a grapefruit-like tasting pith, both carrying very little flavour compounds, but once yeasts come into the equation magic happens. Now the main reason why raw cocoa beans have so little flavour is that the proteins are so tightly bound that everything is trapped in its complex, dense matrix. Right after harvest the resulting mass of beans and pith are left to ferment in the jungle, wild yeasts jump right in consuming the sugars in the pith, creating fantastic new flavour compounds and alcohol, once alcohol is created wild acetobacter varieties join the party and consume the alcohol turning it into acetic acid also known as vinegar

The acid breaks small holes in the bean allowing the yeasts plus other bacteria and fungi to enter the bean and break down this once dense, flavourless object (roughly 150 compounds) to one of the most complex foods in existence. In fact once the fermentation process is complete, the resulting beans contain over 700 new compounds, some of which lead to flavours resembling wine, coffee, vanilla, and other various fruits and spices.

This also means that the oldest preservative in the world, vinegar, wouldn’t exist without this single celled fungi, acetobacter and other acetic acid producing bacteria, like the ones found in kombucha need to feed off small amounts of alcohol, and alcohol is almost always created by yeast. We aren’t talking about alcohol flavour compounds, those are also found naturally in most foods, although yeasts do produce them also.

In the same light, wild yeasts are also responsible for debittering olives and capers, two ingredients which in their raw form are bitter and unappetising. Once placed in a super salty brine magic happens, the salt helps to remove some of the bitterness, and mask some more. But due to the high percentage of salt only a few species of bacteria and fungi can live in the brine, yeasts being a few of them, they start to break up the dense proteins in the ingredients, letting the brine permeate the structure and release even more bitterness into the brine making them edible. In beer brewing different saccharomyces species are used to convert the carbs in the boiled grain broth (known as sweet wort) into alcohol and turning the boring sweet liquid into a delicious, lightly alcoholic beverage.

It’s not only S. Cerevisiae that’s used in beer making, some brewers prefer fermenting at colder temperatures to S. C’s twenty plus Celsius preferred growing range, so these brewers would opt for cold loving varieties like S. Uvarum or S. Carlsbergensis. These varieties also lead to different flavour compounds and one variety like Torulaspora is specifically grown to produce German wheat beers and release very unique flavour compounds not seen in other beer styles.

Yeasts are versatile and can live almost anywhere, so rest assured that if it’s fermented yeast, it’s there working hard to transform a product. Even things like soy sauce, fish sauce and miso rely on yeasts for the majority of their fermentation.

Similarly there are also fungal protists. Protists are single celled organisms that don’t fall under a specific family and don’t really act like plants, animals or fungi, but sometimes they do, these can be fungal like the 800 strong varieties of slime moulds, but they can also be algae or amoebas. But mostly we will be focusing on slime moulds, the smartest single celled organisms, responsible for ruining most of our foods as well as helping scientists and architects design roads and public transport routes in the most efficient way possible, helping us get our foods faster.

We can prevent these protists from destroying our food by low temperature heating, usually at around 48C for a few seconds is enough to kill them off. But one particular variety fuligo septica or in English, “dog vomit slime mould” (I know, terrible name) is actually edible and delicious and is commonly found all over to world, and has the flavour and texture of scrambled eggs. Although I doubt it will be a hit in restaurants any time soon.

Needless to say, if you eat it on a daily basis, if it’s delicious and nutritious, rest assured single celled fungi were probably involved in making it. So lets thank these little creatures for without them our daily staples in the world of food and beverage wouldn’t be possible.

Keith Abela

Keith Abela is a forager, product developer and local food consultant. Who spends all of his time researching the delicious, rare and unique ingredients Maltese nature has to offer. He has a particular interest in multisensory flavour perception and all things fungus.

Click here to see Horeca Issue 14 online